H.E.S.S. Science

Table of Contents

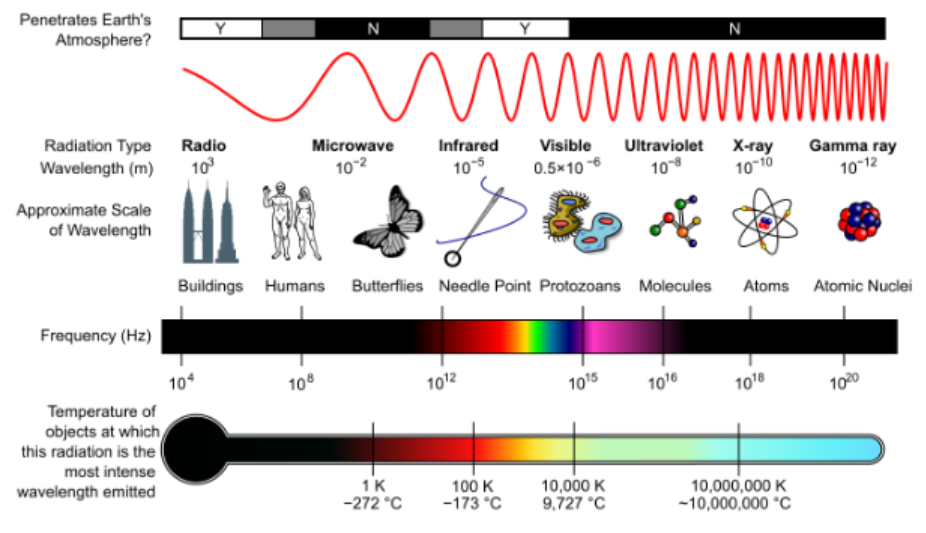

H.E.S.S. is an experiment that observes the sky in high-energy gamma rays. Gamma rays are the radiation with the highest frequency in the electromagnetic spectrum, as illustrated in the following figure:

The frequencies at which H.E.S.S. observes – approximately 1026–1029 Hz – are actually far beyond the range shown in the figure! No object in the Universe is hot enough to emit such energetic radiation, meaning that the gamma rays must be produced “non-thermally”.

In most cases, this involves the acceleration of cosmic rays – charged particles, such as electrons or protons – to extremely high energies. When these cosmic rays undergo interactions with ambient matter or radiation fields, high-energy gamma rays are produced. These gamma rays carry so much energy that they can be registered as individual particles, or photons. H.E.S.S. is sensitive to photons with energies in the range of 0.1–100 × 1012 electronvolts, or Tera-electronvolts (TeV). If you would like to learn more about how H.E.S.S. measures these high-energy gamma rays, please visit this page.

With gamma rays arising from accelerated cosmic rays, the H.E.S.S. telescopes can be used to study cosmic particle accelerators. In fact, high-energy gamma-ray emission has been detected with H.E.S.S. from a variety of objects. Below you can find some of our all-time favourites:

The Crab Nebula

The Crab Nebula is the brightest steady gamma-ray source at TeV photon energies. At its centre resides the Crab Pulsar – a fast-spinning and highly magnetised neutron star that has been left over from a stellar explosion that happened almost one thousand years ago, in 1054.

The pulsar injects high-energy electrons and positrons into the nebula. Through processes called synchrotron radiation and inverse Compton emission, these electrons and positrons emit radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum, up to the energies observable with H.E.S.S.

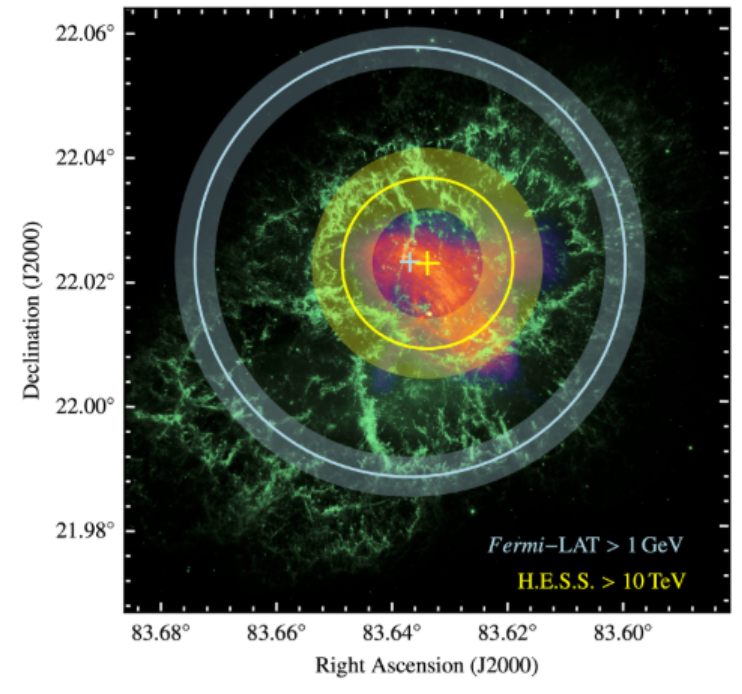

Because it is so bright, the Crab Nebula is often used as a “calibration source”. A performance study carried out on the Crab Nebula [A&A 457, 899 (2006)] is among the most-cited H.E.S.S. papers. More recently, the extent of the nebula could be measured in the gamma-ray domain for the first time (see picture), which enabled constraining the strength and shape of the magnetic field in the nebula [Nature Astronomy 4, 167 (2020) and A&A 686, A308 (2024)].

More information: HESS SOM 2017-10, HESS SOM 2012-12, HESS SOM 2004-10.

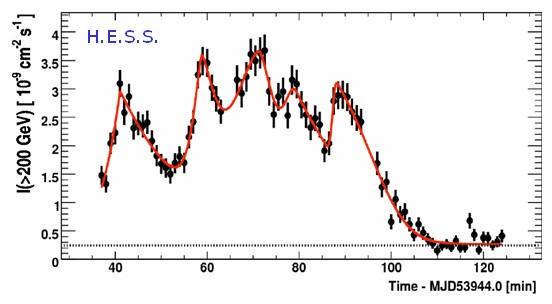

The prototypical blazar PKS 2155–304

On the night of 28 July 2006, the blazar PKS 2155–304 entered an exceptionally active state, producing one of the most dramatic very-high-energy (VHE) γ-ray outbursts ever observed from an extragalactic source. The H.E.S.S. telescope array observed the source at fluxes exceeding seven times the Crab Nebula above 200 GeV – a level of luminosity unprecedented for a high-frequency-peaked BL Lac object.

What distinguished this episode was not merely its intensity but its extraordinary temporal structure. The γ-ray emission displayed pronounced variability on minute-level timescales, with individual sub-flares rising and decaying on characteristic times of roughly 200 seconds. Such rapid fluctuations imply an emitting region of extreme compactness: at face value, smaller than a few 1014 cm if conventional causality arguments apply.

To sustain the observed luminosity within such a confined region, the jet must be both highly collimated and relativistically boosted, requiring Doppler factors of δ ≳ 50–100. These values far exceed those typically inferred from broadband spectral modelling of blazars, challenging long-standing assumptions about jet dynamics and internal opacity.

Nearly two decades later, the 2006 outburst of PKS 2155–304 remains one of the most striking demonstrations of rapid, high-amplitude variability in the TeV sky. It continues to inform theoretical efforts to understand particle acceleration and radiative processes near supermassive black holes, as well as the complex substructure of relativistic jets. The event stands as a benchmark for future observations, which may determine whether such extreme behaviour is rare – or simply awaiting more sensitive instrumentation to be revealed.

More information: HESS SOM 2004-11, HESS SOM 2009-02, HESS SOM 2016-10.

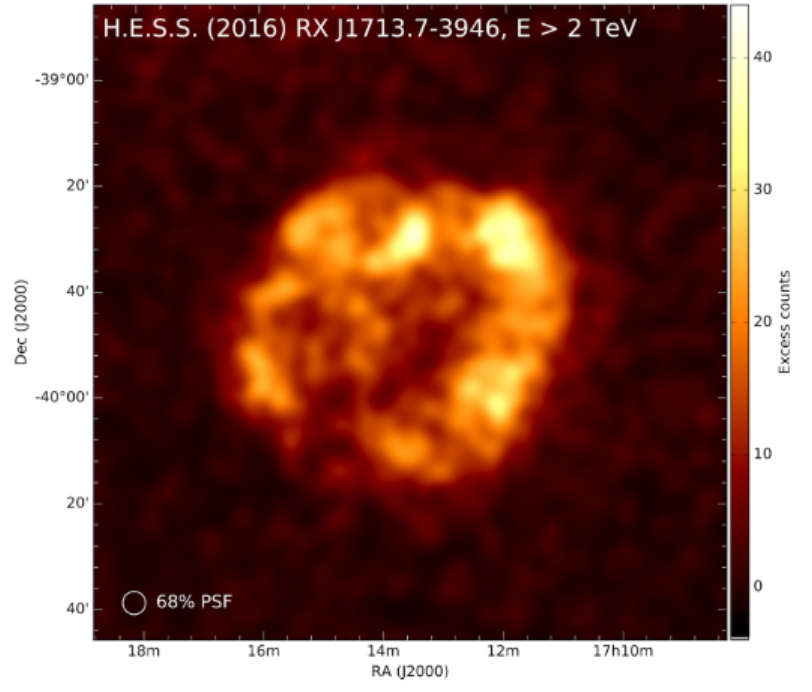

The supernova remnant RX J1713.7–3946

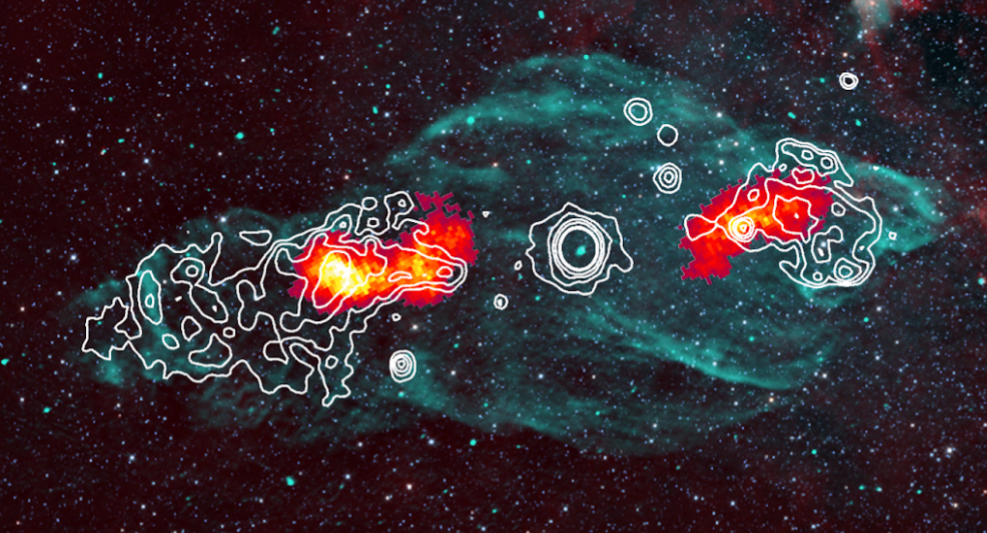

RX J1713.7–3946 is the remnant of another supernova explosion that occurred approximately a thousand years ago. In this case, however, it is not a neutron star that powers the emission. Rather, the gamma radiation is thought to be produced by cosmic rays that are accelerated at the shock front running outwards as a result of the explosion. This results in a shell-like structure of the emission, nicely visible in the image.

RX J1713.7–3946 is the first TeV gamma-ray source that could be spatially resolved at these energies [Nature 432, 75 (2004)] – previously detected sources had always appeared as point-like objects. Since then, several more shell-type supernova remnants have been found with H.E.S.S.

In the latest H.E.S.S. publication on RX J1713.7–3946 [A&A 612, A6 (2018)], first indications for an escape of particles from the shock acceleration region were found. This conclusion could be drawn from a comparison of the H.E.S.S. gamma-ray image with an XMM-Newton X-ray image – a nice demonstration of how insights about astrophysical objects can be gained from combining observations at different wavelengths.

More information: HESS SOM 2005-01, HESS SOM 2016-09

The microquasar SS 433

SS 433 is a binary star system in which a black hole, with a mass approximately ten times that of the Sun, and a star, with a similar mass but occupying a much larger volume, orbit each other with a period of 13 days. The intense gravitational field of the black hole rips material from the surface of the star, which accumulates in a hot gas disk that feeds the black hole. As matter falls in toward the black hole, two collimated jets of charged particles (plasma) are launched.

The jets of SS433 can be detected in the radio to x-ray ranges out to a distance of less than one light year either side of the central binary star, before they become too dim to be seen. Yet surprisingly, at around 75 light-years distance from their launch site, the jets are seen to abruptly reappear as bright X-ray sources. The reasons for this reappearance have long been poorly understood.

Until recently, no gamma ray emission has ever been detected from a microquasar. But this changed in 2018, when the High Altitude Water Cherenkov Gamma-ray Observatory (HAWC), for the first time, succeeded in detecting very-high-energy gamma rays from the jets of SS 433. This means that somewhere in the jets particles are accelerated to extreme energies.

Prompted by the HAWC detection, the H.E.S.S. Observatory initiated an observation campaign of the SS 433 system. This campaign resulted in around 200 hours of data and a clear detection of gamma-ray emission from the jets of SS 433. While no gamma-ray emission is detected from the central binary region, emission abruptly appears in the outer jets at a distance of about 75 light years either side of the binary star, in accordance to previous X-ray observations.

The Galactic Centre

The central regions of our own galaxy contain many important and mysterious objects. First among them is the central supermassive black hole (Sgr A*) ‘Sagittarius A star’, millions of times more massive than the sun but – unlike the black holes in many other galaxies – in a rather quiet state currently. Nonetheless, Sgr A* may be responsible for the TeV gamma-ray emission we see from the region, both directly at the position of Sgr A* and in the surrounding dense molecular clouds known as the ‘central molecular zone’ or CMZ.

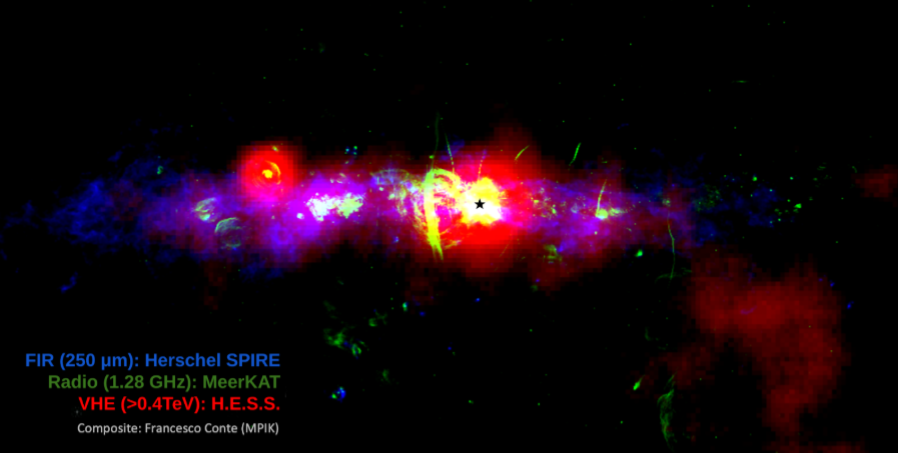

The composite image below shows the Galactic Centre region at infrared wavelengths (red), in the radio domain (green), and at high-energy gamma rays measured with H.E.S.S. (red).

The diffuse emission seen with HE.S.S. from the CMZ is thought to originate from collisions of accelerated cosmic rays with the dense gas clouds. Studying it, we can learn about where the cosmic rays are accelerated, and how they propagate throughout the CMZ.

Even more exciting is possibility to determine the particle nature of Dark Matter via observations of the Galactic Centre region. Dark matter models predict that the density of dark matter close to the Galactic Centre is large enough such that dark matter particles may annihilate and produce gamma rays that can be distinguished from the (non-dark-matter-related) foreground emission.

More information: HESS SOM 2004-12, 2006-03, 2009-12, 2016-04, 2018-02, 2020-11, 2022-09.